Introduction to Capability Concepts

Page Tags

The Capability systems and models variations date since middle half 60’s. Despite being classical, this model still needs to conquer widespread use today, due its straightforward reasoning properties and secure communication patterns (even among mutually suspicious parties). For those who don’t know that model, this post suits well as a complete introduction and essay (in some sense) about Capabilities, related terms/concepts and design issues. So, let’s explore this Capability world together!

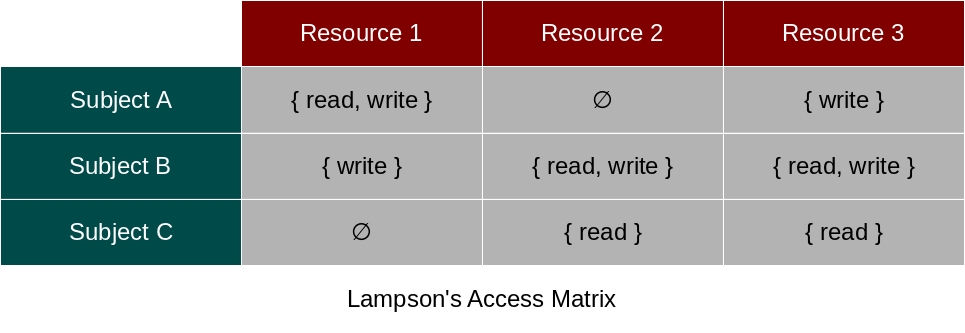

Before we dive in such model, we must know how systems are built around security concerns. The main security concern of many systems is all about who will/can access what and how. An important tool to reason about said concern is known as Access Matrix.

Access Matrix

The Access Matrix is a table where columns are resources (i.e, what) and rows are subjects (i.e, who – in the classical literature they are

called as domains). Every entry in this table

denotes a resource privilege (i.e how) associated with given subject. The privileges enforce how a resource is manipulated by the subject. Also,

subjects cannot use more privileges than the described in their associated set of privileges. Below, an illustration of such Access

Matrix with the most basic privileges (read and write):

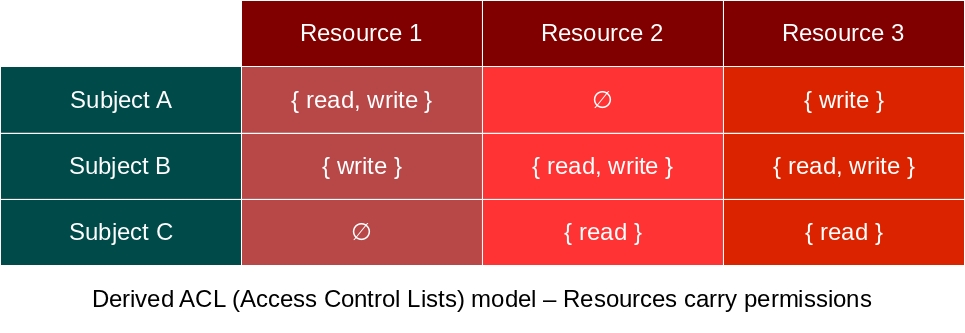

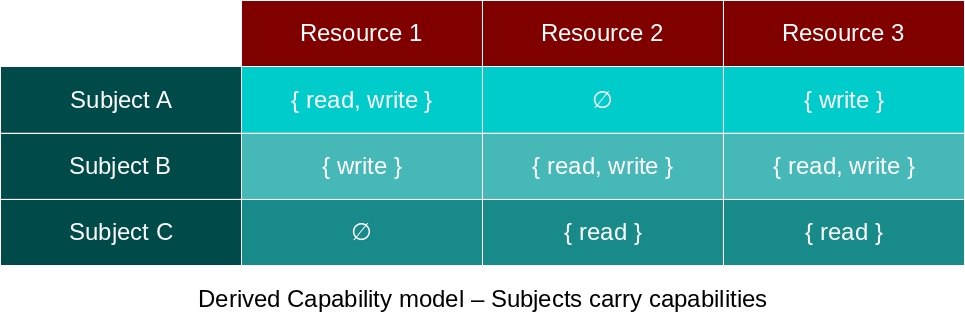

When we are going to implement such security tool as a mechanism, there is an important question that arises: where we’ll implement these privileges? It seems that there are only two options: either in the resource itself or in the subject part. But, whatever option is taken, it has a profound impact on the initial model and result system. So, these impacts are derived from interpretations of said Access Matrix – the interpretation itself is the solution for the previously asked question. One interpretation is known as ACL model while the other (that we’ll focus from now on) is known as Capability model. The possible interpretations follow:

The ACL model is well known and widespread among many Operating Systems and Programming Languages, surely you may already know it (although possibly never through this name). The Capability model, on the other hand, is a rather unknown model where everything is a Capability (that is, everything is a resource attached with privileges). While the ACL model works mostly through Authentication, Capabilities work by Authorization (i.e, sharing/delegation of resources to other subjects).

It’s also important to remind: Capability models have a subjects-as-processes interpretation instead of the subjects-as-users interpretation known in the ACL model. Due this reason, you can easily conclude that the ACL model provides coarse-grained access control while Capabilities themselves are fine-grained access control mechanisms. These subjects interpretations are requirements for both models, once we have leaved these requirements, we’re out of the respective security model.

We’ll defer the analysis of many choice impacts along this post, but the trivial impact/implication is that:

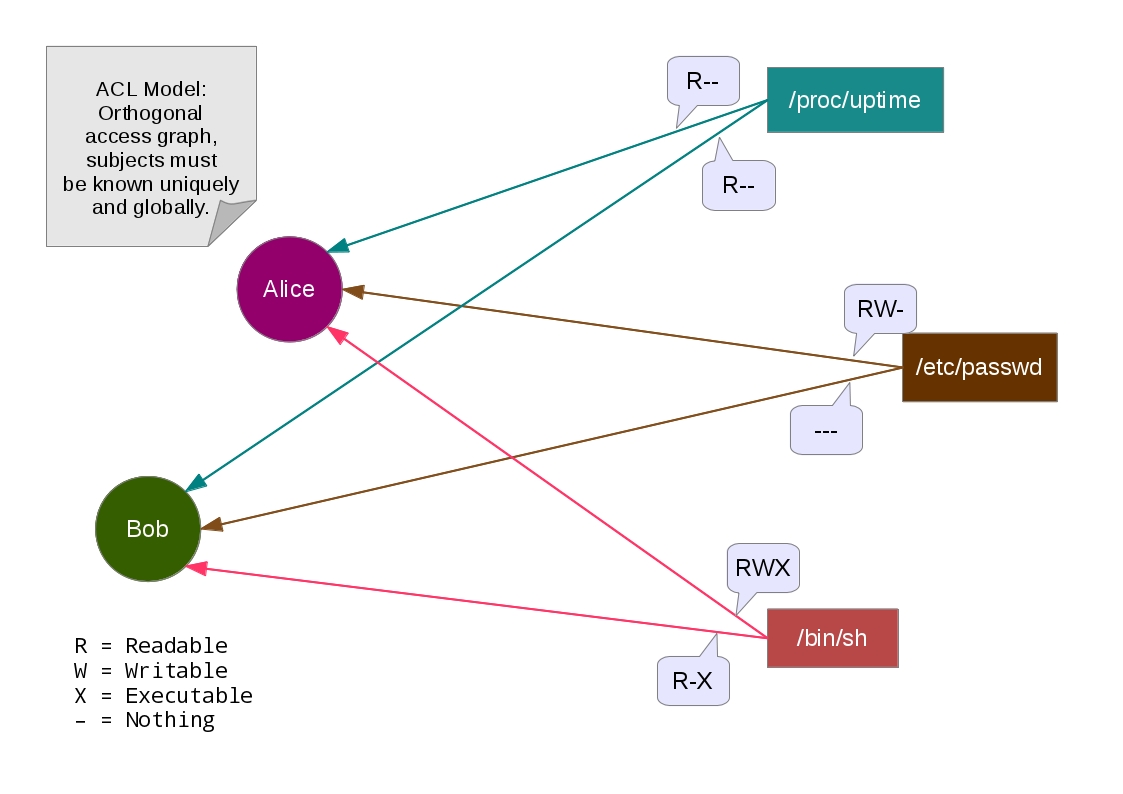

- The ACL model is very static, orthogonal-to-the-system and nominal in its nature, while;

- The Capability model is rather dynamic, unified-into-the-system and structural in its own right

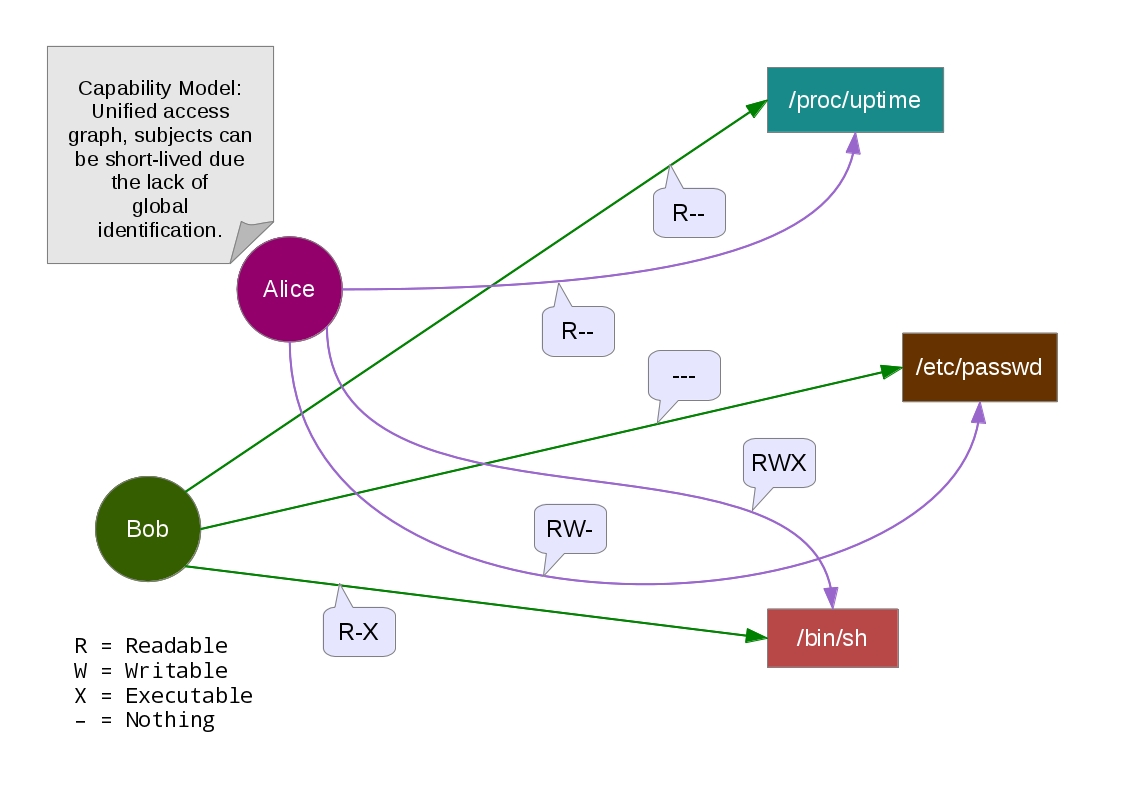

By “Orthogonal access graph” and “Unified access graph”, we mean how naturally seem these pointers. In the Capability Model, the

Access Graph is unified with the Reference Graph, thus, an external security mechanism/feature to control the access isn’t necessary.

On the other side, the ACL Model requires beforehand a global identification together with some administrator of these accounts (is the duty of

the administrator to amplify, grant or revoke rights – these administration rights are known as a control/owner privilege). Therefore,

dynamic/ephemeral subjects aren’t feasible in the ACL Model anyways due the explicit labeled authentication of subject names/identifiers.

Speaking of nominal things, there is a feature in which we want to avoid in all the cost. This (anti-)feature is called Ambient Authority.

Ambient Authority

A system contains Ambient Authority when some subject just use an (almost) unique & freely available name to access anything. This occurs

frequently in ACL-based security, for instance, when we open a file. It also occurs on global/public APIs taking too much responsibilities &

privileges, e.g, Reflection APIs.

The classical open function is also an example of undesirable public API, because it gives you the power to open any file in the

filesystem through the .. notation (which change the current directory to one above) – but only if you have the proper rights (and it’s

possible for a malicious user to acquire the same rights of someone else through authentication). If you want to know why the .. notation, the

absolute directory lookup or even the $HOME lookup are really bad, just google

PHP Remote File Inclusion to take a glimpse of the incoming answer. These notations are just

good examples of Ambient Authority.

Ambient Authority arises due the separation of designation from authority. This separation is the rule of thumb in ACL-based systems, where

you can acquire an implicit authority over a reference without the known introduction beforehand to use it (that is, your client can’t deny, revoke,

amplify, control, restrict or disable what you are willing to take from him). Permissions here are useless,

‘cause they often deal directly with the right to access,

not with the right to exercise such authority.

It’s important to remember that authority doesn’t mean permission: authority is a “generalization” of permission in some way.

Where permission stands for the direct means to acquire rights over a resource, authority also includes the

potential effects for “abuse” of indirect means to acquire that same rights. That is, permission deals directly with the identity of the

sender/owner subject, where authority will also pay attention on the indirect means to bypass security through message-passing. In the message-passing

layer, if you don’t trust someone else, you will often deliver revocable references/proxies to this guy.

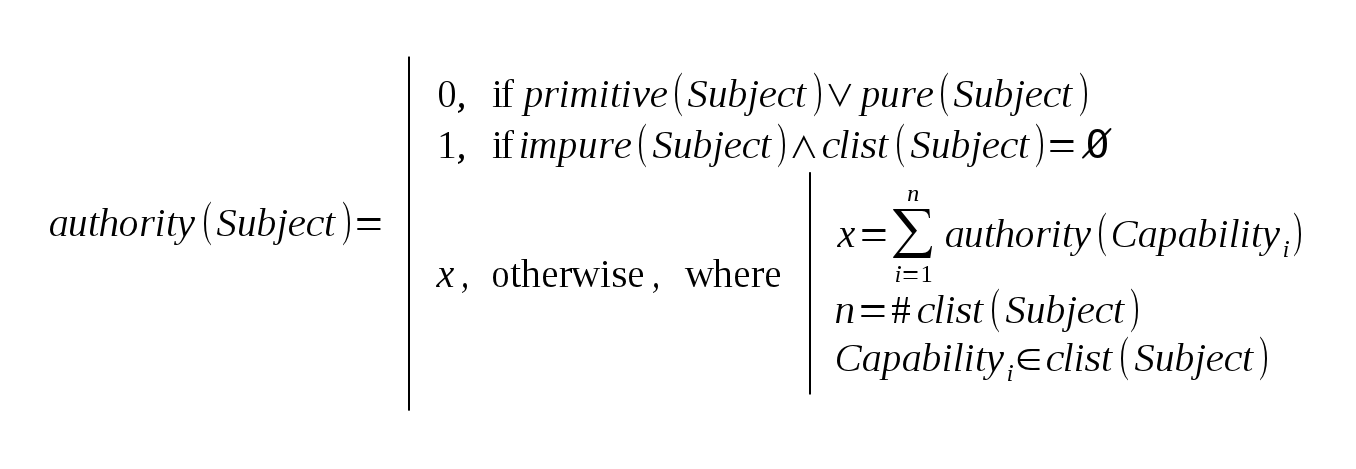

Let's represent pure capabilities as green nodes in the reference graph and impure capabilities as orange ones. A fact that we can derive from this is that

green nodes can't point to orange ones, otherwise they must be impure, and thus, orange instead green (remember that authority is propagated up to the

graph). But it's not true on real cases, 'cause if there is a permission to access the source of authority, this permission embodies the source of authority

and the subject becomes another source for this authority. As you can see, it is possible to exist many sources of the same authority so long as the

respective permissions reveal them. In other words, you can expose a pure object pointing to an impure one, the pure object is pure if it will never access

any impure parts of its held impure objects -- the pure object has none authority (despite the held sources of authority) 'cause it is ensured to never

exercise any authority, even the authority to delegate these authorities.

Back to the reference graph, it is even possible to turn this graph into an hierarchical tree, we must only transitively split shared

capabilities into different nodes, but identify them with the same label and provide unique labels for different capabilities. It, thus, give us the power

to represent aliases (edges pointing to shared nodes) as objects (nodes sharing an identity).

Let's represent pure capabilities as green nodes in the reference graph and impure capabilities as orange ones. A fact that we can derive from this is that

green nodes can't point to orange ones, otherwise they must be impure, and thus, orange instead green (remember that authority is propagated up to the

graph). But it's not true on real cases, 'cause if there is a permission to access the source of authority, this permission embodies the source of authority

and the subject becomes another source for this authority. As you can see, it is possible to exist many sources of the same authority so long as the

respective permissions reveal them. In other words, you can expose a pure object pointing to an impure one, the pure object is pure if it will never access

any impure parts of its held impure objects -- the pure object has none authority (despite the held sources of authority) 'cause it is ensured to never

exercise any authority, even the authority to delegate these authorities.

Back to the reference graph, it is even possible to turn this graph into an hierarchical tree, we must only transitively split shared

capabilities into different nodes, but identify them with the same label and provide unique labels for different capabilities. It, thus, give us the power

to represent aliases (edges pointing to shared nodes) as objects (nodes sharing an identity).

Although “Capability-based” implies “Non-Ambient Authority”, it’s worth to note that “Non-Ambient Authority” doesn’t imply “Capability-based”. Ambient Authority must be eliminated from the system ‘cause it is prone to two major problems:

- The Confused Deputy Problem (the PHP Remote File Inclusion is also an instance of this problem)

- The break of the Principle of Least Privilege

Principle of Least Privilege

Also known as Principle of Least Authority (POLA), this principle states that subjects must only use the minimum, needed and legitimate resources to complete an ongoing task. This principle also reduces the probability of misuse of resources. To achieve that principle, we must ban Ambient Authority (which provides implicitly passed resources) in favor of explicit communication/message-passing. When this principle is not achieved (i.e, broken), it’s a matter of faith to rely on a bunch of passed privileges being enough and properly used by the subject.

Confused Deputy Problem

Also known as Luring Attack, the Confused Deputy Problem stands for the fooling of a deputy (here, a subject carrying some possibly sensible capabilities) by an attacker. In simpler words, the attacker guides the deputy into the misuse of its own capabilities. “Misuse” here means the use in such way that violates the expected purpose / original intent, and, therefore, allowing something which shouldn’t. This problem is due the trust relation being abused: the Capability model can’t eliminate this problem, but instead reduces given occurrences while the ACL model is very prone to this problem.

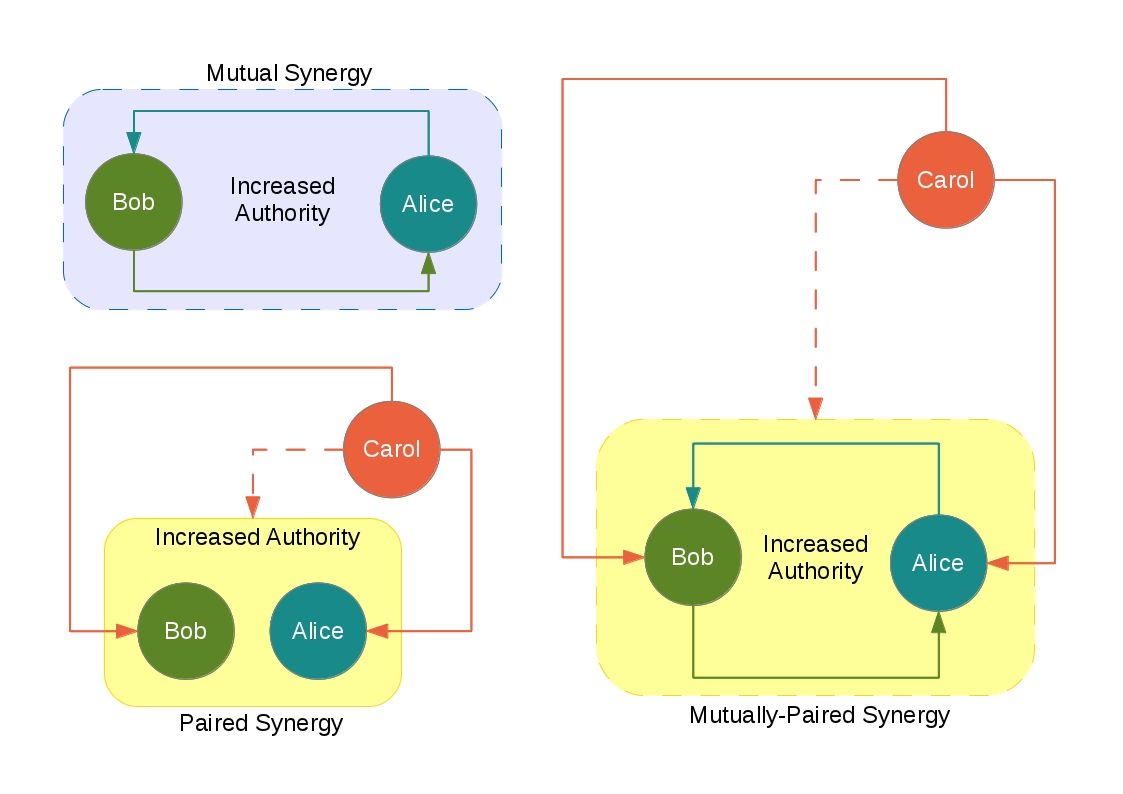

Synergy

Synergy is an implicit pattern that often occurs in Object-Capability Systems. This pattern is very important on such systems, because it states that the composition of 2 introduced capabilities results into a new one. There are many forms appearing in Capability-based systems in which this pattern manifests itself, such as:

- Rights amplification

- Sibling communication

- Sealing/branding pairs

- Identity/equality comparison

- And even in the introduction of capabilities (a.k.a, delegation of capabilities)

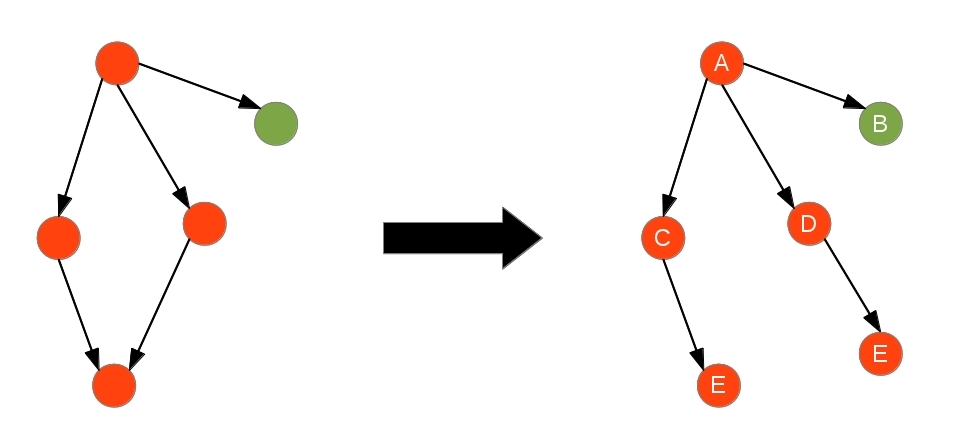

Informally (I mean, not a standard / official / literature-based classification), I will give 3 kinds of synergy classified as below:

- Mutual Synergy, some capability introduces itself to another capability and also is introduced for this other one

- Paired Synergy, the introduction of 2 capabilities results into a new held capability for the subject

- Mutually-Paired Synergy, the subject introduces both capabilities to themselves and acquire the result capability

The image below may help you to understand that:

An good example of synergy can be a file handler: when we have both readable and writable views of a handler, it’s possible to

acquire a third view of that handler (one performing append). A simple (“Sure?”) & expressive (“Enough!”) code in an unexpected & unsafe language

follows (the code below is assumed to be slow, but a buffered implementation will speed up the often usage):

package marcoonroad.capability.synergy.filehandler;

public interface ReadableStream {

public String read ( );

}

package marcoonroad.capability.synergy.filehandler;

public interface WritableStream {

public void write (String content);

}

package marcoonroad.capability.synergy.filehandler;

public interface AppendableStream {

public void append (String content);

}

package marcoonroad.capability.synergy.filehandler;

public final class SinergyStream

implements ReadableStream, WritableStream, AppendableStream {

private final ReadableStream readable;

private final WritableStream writable;

public SinergyStream (ReadableStream readable,

WritableStream writable) {

this.readable = readable;

this.writable = writable;

}

// IDE won't complain

@Override

public String read ( ) {

return readable.read ( );

}

// IDE won't complain

@Override

public void write (String content) {

writable.write (content);

}

// IDE won't complain

@Override

public void append (String content) {

String previous = this.read ( );

this.write (previous + content);

}

}

Although the passed views can point to unrelated system resources, once they’re put together, they’re seen as just one thing.

Surely, you may ask yourself if it’s safe to use this capability possibly made of distinct/different capabilities, but it’s one

of the general ideas of the Capability model. If we pass a writable view to the null device, the effects of the null device

will be propagated to the append operation, that is, this won’t cause any interference on the composed readable view. You will never

know, anyway, if any introduced capability is either a virtual or concrete one – this gives the power to the client run your code

in an isolated environment for testing or sandboxing, it’s only your responsibility to believe that the introduced capabilities are

real system resources (but don’t rely on it).

Notice that ReadableStream and WritableStream capabilities imply also AppendableStream, but not the other way around.

It means that synergy is not a symmetrical/reversible arrow (except – in some sense – if facets are living around), although

commutative on co-domain & domain, and also transitive. In formal notation, synergy is a mapping from the Cartesian product of

2 capabilities into a triple preserving the initial capabilities plus a third one, e.g:

(* structural interface refinement/restriction *)

module type ICapability = sig

type capability (* capability is abstract *)

end

module type ISynergy = sig

include ICapability

(* internal structural type aliases *)

type 'value pair = 'value * 'value

type 'value triple = 'value * 'value * 'value

val synergy : capability pair -> capability triple

end

Synergy here is described working on 2 capabilities, but it’s straightforward to generalize that into more provided capabilities,

mostly because synergy is a composable property. Other examples of synergy are the file copy and remove operations: together

they yield the file move operation. We have already seen how to compose small building blocks, now let’s see how to make these

small building blocks with facets.

Facets

Facets are a kind of first-class “redecorators”, which provide a subset of decorated capability’s interface (may it be an “adaptor” which reduces the exposed interface to the minimum and needed?). This mechanism fulfills some part of the Least Privilege Principle (the non Ambient Authority fulfills the rest), and, thus, reduces the occurrences of the Confused Deputy Problem. Facets can also act like Proxies and, almost any Object Oriented Programming Language supports this kind of pattern, either explicitly or implicitly, through object wrappers. The use of facets to restrict interfaces (and also behaviors) from Capabilities is often called as attenuation.

In the image above, facets are like “restricted views” of some capability. Facets can also “wrap” other facets, it is due the fact that facets (i.e, decorators/proxies) and capabilities (i.e, objects) are seamlessly indistinguishable. For this reason, identity comparison is considered bad due, for example, two distinct facets sharing the same decorated object, so:

- in one hand, they’re different because the interface differs,

- on the other hand, they point to the same internals…

How can us compare these facets properly? Statically typed languages only allow comparison on values of the same type/interface, but it doesn’t work when we have dynamic interfaces (what facets are actually). The solution simply is to ban “external” identity (that is, capability comparison/discrimination on the programmer-side) while we still retain “internal” identity for the GC, Auditing, Capability Revocation, etc. Comparison on primitives such numbers and strings are needed in some way, so the ban here doesn’t count.

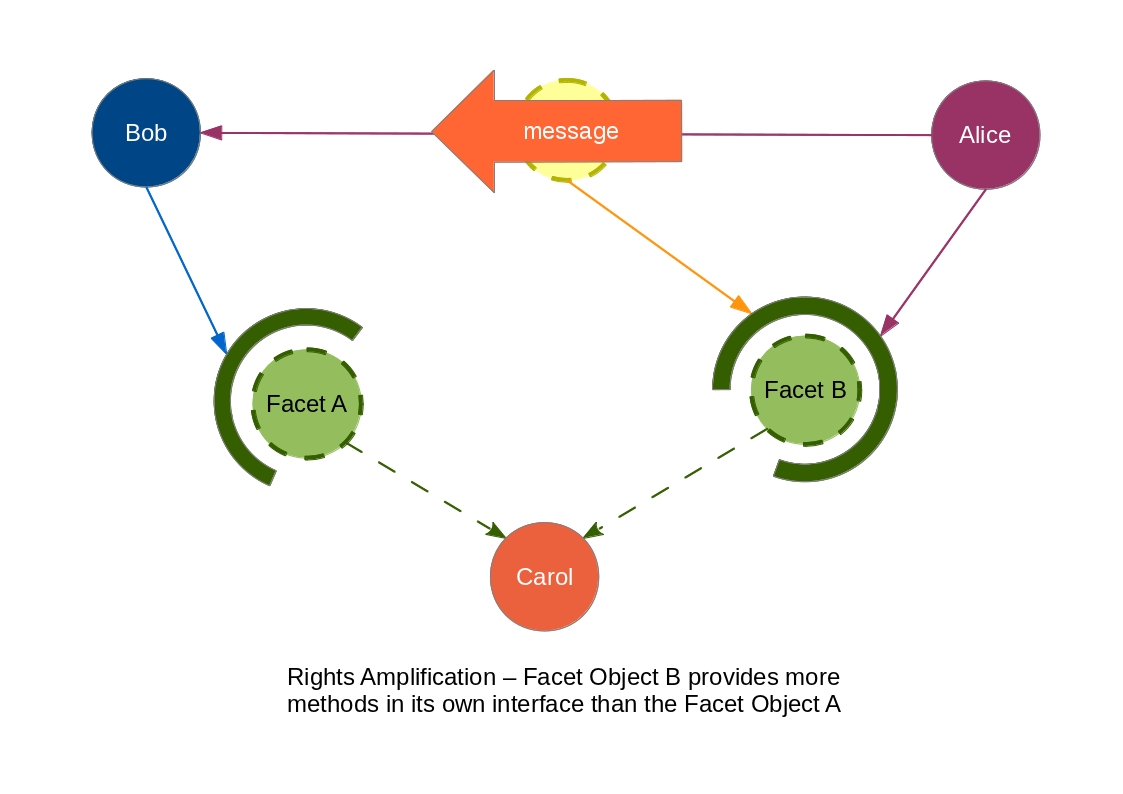

Rights Amplification

Rights amplification occurs when we provide additional authority over some system resource through a new capability. The image above captures pretty well that idea.

Sibling Communication

This name may sound like a kind of message-passing protocol, but it’s just an alias for closures in the Object Capability Model. By closures, I mean the most accurate thing to the used definition: 2 parties sharing the same behavior set. If this behavior (set of methods, on most cases) results from the evaluation of another behavior set (that is, they are closures), it means that they share the internal state of this super-behavior. Thus, the “siblings” are aware of performed changes on one of these “secretly shared” states. This, therefore, is a form of secure communication (if no loopholes are freely accessible, such as the reflection for debuggers inspecting the call stack), and also a kind of “lexical” Synergy. Siblings are often used to build other forms of Synergy, though.

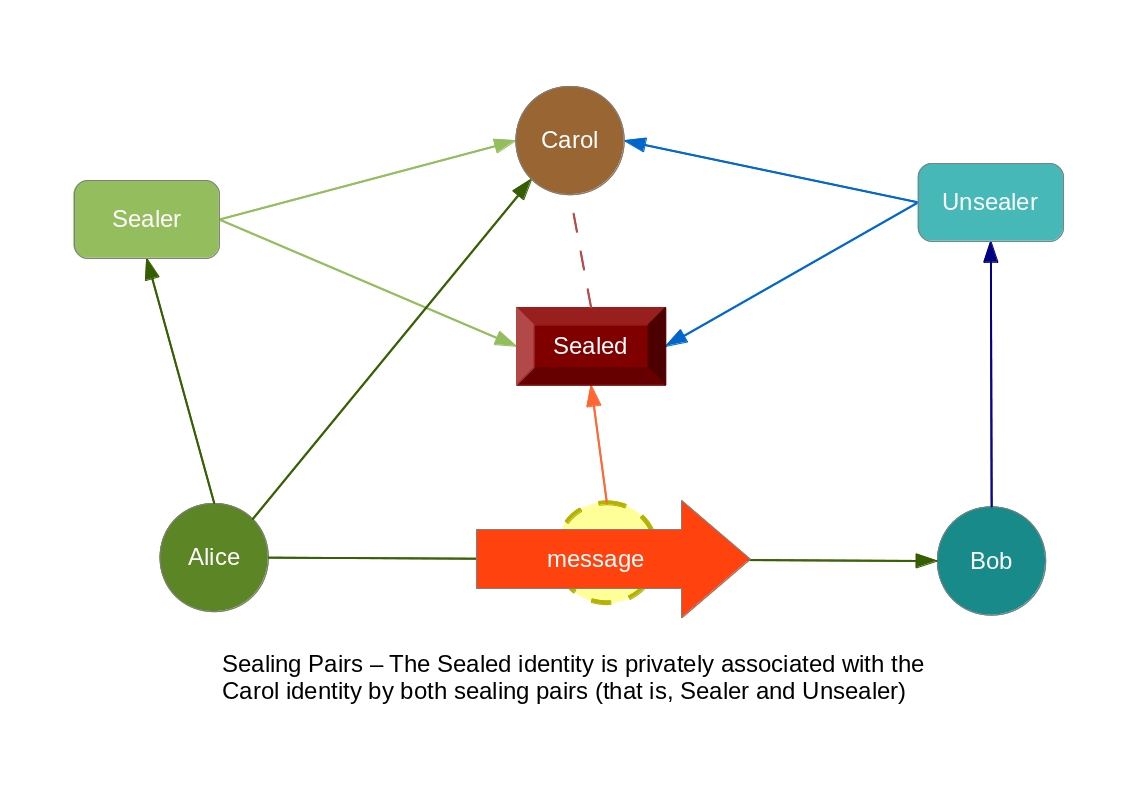

Sealing Pairs

Also known as seals (and introduced in the classical paper Protection in Programming Languages), sealing pairs are a pair of functions

[ seal, unseal ] which act like as the encryption & decryption algorithms of some given message, respectively. In the programming

language context, there’s no such encryption mechanism, an encrypted message is just an unique object with an empty interface. ‘Cause this

unique object provides an unique identity, we can use internal hash comparison, together with Sibling Communication (i.e, closures) to

implement sealing pairs, and, therefore, achieve Rights Amplification with that.

Note that, however, identity is not a requirement to build sealing pairs: the programming language Noether itself uses unique alpha-renames on the ‘Static Names’ mechanism to provide safe compile-time encapsulation of resources.

function sealing (label) {

let map = new WeakMap ( );

let result = { };

result.seal = function (object) {

let sealed = { };

sealed.toString = function ( ) {

return "<sealed by " + label.toString ( ) + ">";

};

map[ sealed ] = object;

Object.freeze (sealed);

return sealed;

}

result.unseal = function (sealed) {

let object = map[ sealed ];

if (object === undefined || object === null) {

throw "Invalid sealed reference!";

}

else {

return object;

}

}

return result;

}

I must also give you some advice, though. Don't abuse of the Rights Amplification concept unless you want to be prone to Luring Attacks (do you remind the said loopholes in synergy?), right?

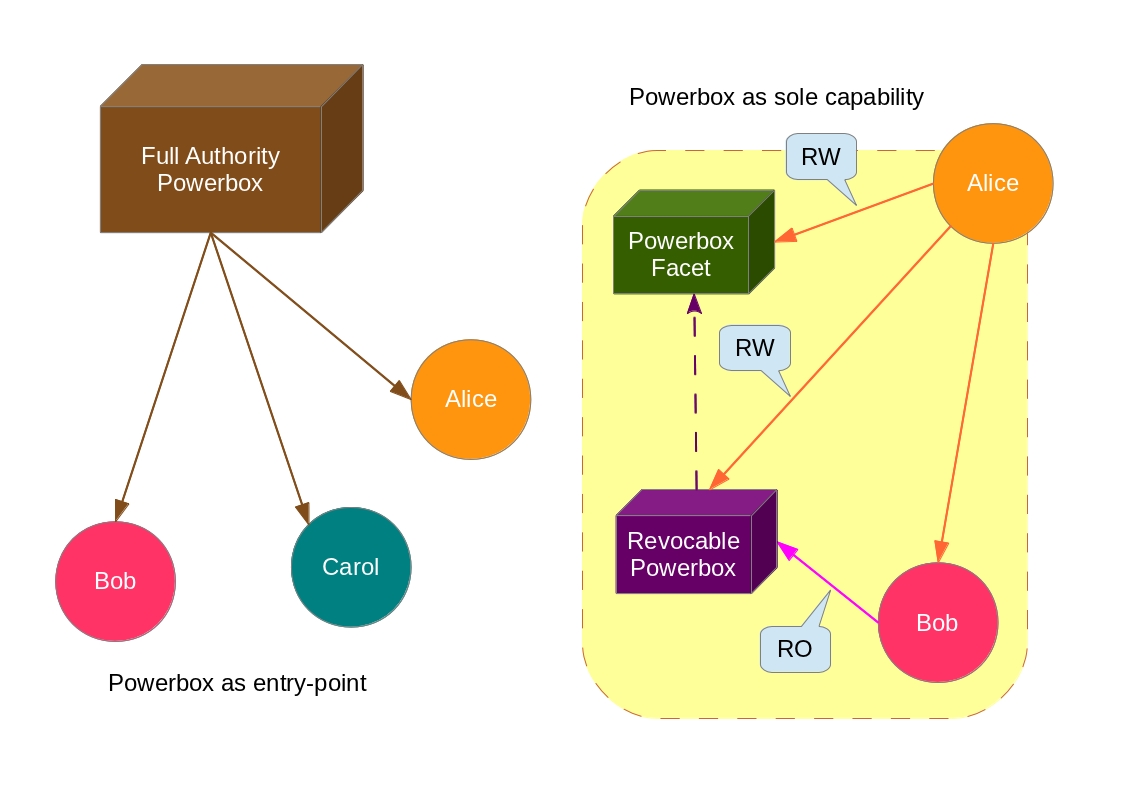

Notes on implementations

Implementations of the Object Capability Model in the PLT (Programming Language Theory) field frequently are either pure new programming languages or subsets of already existent ones. The subset design provides a “tamed” API together with a “Powerbox”. The tamed API stands for the “Capability-safe” set of functions, classes, etc. that can be exposed globally without further problems (that is, they describe resources of the programming language itself rather than Operating System resources, for example: vectors, lists, sets, bags and maps data types). Resources which must be encoded as Capabilities are passed explicitly through message-passing (e.g, an object dealing with the sensible business logic, such as passwords, telephones, emails, and so on). On the other side, the Powerbox is the bridge which fulfills the gap between the tamed API and the OS environment. It may be thought like the “entry-point” of the application (more specifically, like the injector of the well-known Dependency Injection pattern), but sometimes it is also a revocable introduced capability (a kind of mediator in the Mediator design pattern). The Powerbox will often carry a description of prone-to-be-accessed Operating System’s resources, this description list itself acts like a white-list approach for sandboxing (note that the sandbox and powerbox differs somehow, while the former controls the access for the environment, the latter embodies the environment as a capability). So, every external code is loaded as if it were a client module attached with deferred requirements – the role of the Powerbox is to resolve explicitly these requirements with some parcel of its full authority.

In the Capability model, rather than providing a complete set of security mechanisms, we provide minimal abstractions to build high-level security abstractions (that is, enforcing policies on top of these “primitive” ones). This idea works in the same way of layered abstraction of modules. The great profit and benefits of that security approach is the possibility of decouple and compose abstractions in diverse ways as if they were LEGO’s building blocks.

In his PhD thesis Robust Composition, Mark S. Miller discusses about loader isolation (i.e, “environment-based” eval). It turns out that every language

providing this kind of loader as function, can also provide a modular Capability integration of code (only if magic names aren’t resolved implicitly

such as namespace/package-level identifiers). Some languages fit these requirements, for example the Scheme and Lua programming languages. Otherwise, the

Meta-Circular Interpreter “pattern” known in the Lisp’s world can be used to “reveal” the internals of a given Programming Language and, thus, tweak a

runtime resolution of unbound names (although this pattern is very hard – if not impossible – on languages without “unified” syntax in the same sense

of Lisp/Forth syntax – a.k.a, a syntax without keywords). Compile-time type systems and bytecode monitoring can also be used to enforce minimal and safe

Capability policies, anyways, but the control over such accesses is in the hands of the implementation rather than user’s hands.

Final remarks

The Capability Model is a great model that deserves some attention. It can be an useful feature in Operating Systems and Programming Languages. System Designers should be aware of that, in the end, the gains overcome the costs of this security model. I hope, at least, that you have enjoyed this post (despite my worse English vocabulary), and, if possible, thought with care about the whole thing. Who knows, you may also wish to implement a Capability System, either as a Programming Language subset framework or, even a new Programming Language with the needed support from scratch?

If you really liked this post, you can share it with your followers or follow me on Twitter!

References

- Capability Myths Demolished, 2003 - Mark S. Miller, Jonathan Shapiro and Ka-Ping Yee

- Protection in Programming Languages, 1973 - James H. Morris Jr.

- Protection, 1971 - B. W. Lampson

- Robust Composition: Towards a Unified Approach to Access Control and Concurrency Control, 2006 - Mark Samuel Miller

- How Emily Tamed the Caml, 2006 - Mark Miller and Marc Stiegler

- The Oz-E Project: Design Guidelines for a Secure Multiparadigm Programming Language, 2005 - Peter Van Roy and Fred Spiessens

- Permission and Authority Revisited: towards a formalisation, 2016 - Sophia Drossopoulou, James Noble, Mark S. Miller and Toby Murray

Further reading (external links)

Updated on May 5, 2017